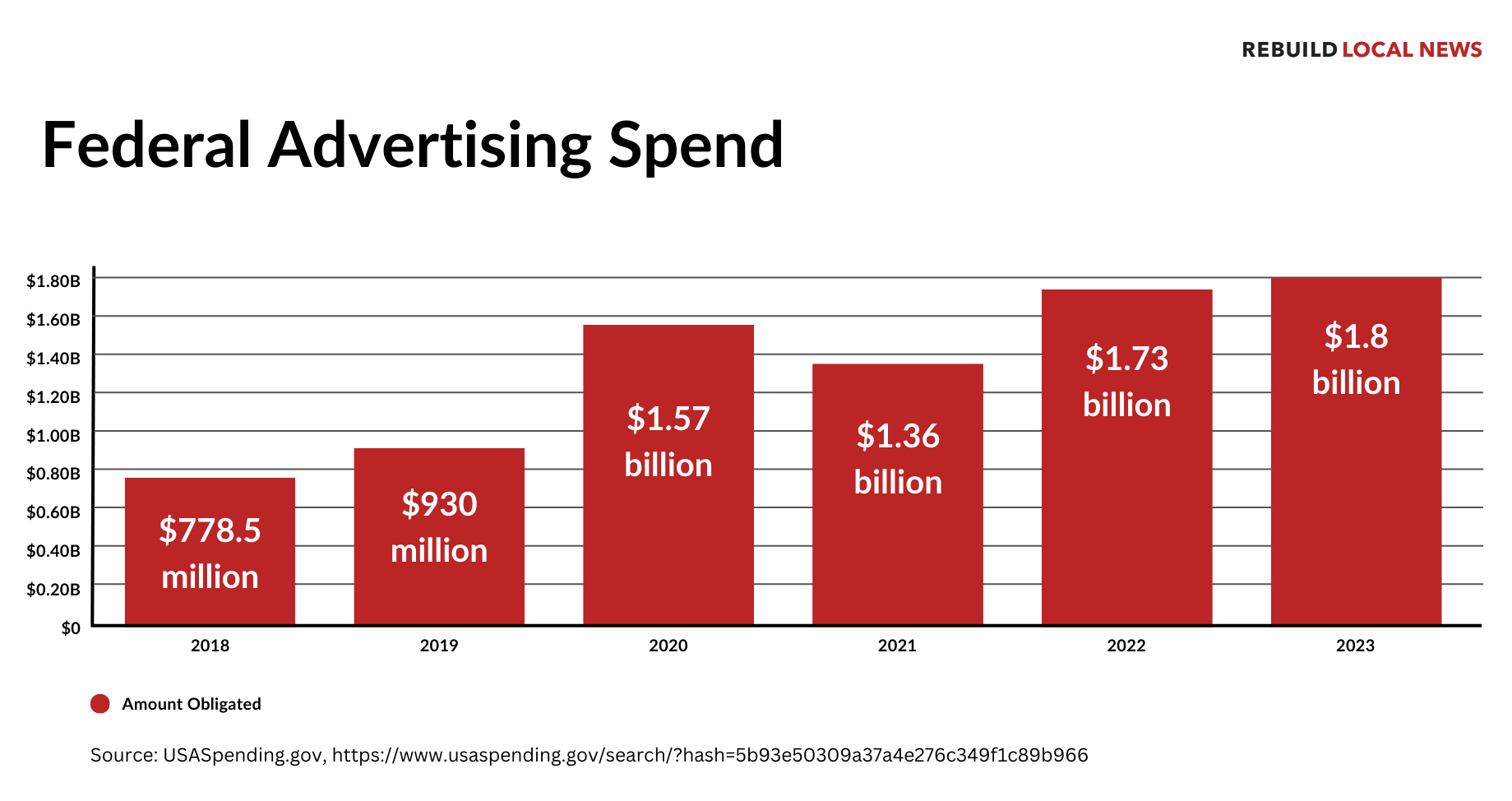

Federal Government Advertising Spending Has Doubled to $1.8 billion since 2018

But little is known about what types of media receive federal advertising spending, whether it’s effective, and whether it could be leveraged to help alleviate the crisis in local news.

Executive Summary

Federal government agencies in the United States spent more than $1.8 billion on discretionary advertising in 2023 – more than double the 2018 spend, according to federal procurement records analyzed by Rebuild Local News.1 The increase from the $778.5 million agencies spent on advertising in 2018 was driven by multiple forces, including the COVID-19 pandemic response, inflation, and increased efforts around military recruitment.

This is potentially significant because efforts to save local news around the country have noted that small shifts of government advertising toward more community based media can have profound positive effects. The growth of federal advertising spending raises the question of whether funds could be allocated in ways that allow agencies to meet their important marketing goals, while simultaneously helping sustain local news.

Unfortunately, we also found that there is a debilitating lack of transparency in how federal advertising money is spent. It is unclear how much is going to social media companies compared to national or local media. The lack of transparency makes it harder for smaller media to make the case for inclusion in advertising buys, and, in general, increases the odds of corruption or ineffectiveness.

This paper calls for better disclosure of federal agency advertising spending to inform the public about which companies are benefiting from public dollars, to allow better monitoring of the spend to guard against cronyism and waste, and to offer better evidence for the effectiveness of agencies’ advertising with media, including local community news outlets. It also considers the merits of requiring the government to set–aside some advertising funds for community news outlets when possible.

Top Federal Advertisers

Rebuild Local News reviewed five years worth of limited government advertising budget data available through the USASpending.gov database maintained by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service. Our search included all agency spending under the Product Service Code (PCS) R701 Support – Management: Advertising from 2018-2023. The database provided overall totals of advertising spending broken down by year and by agency.

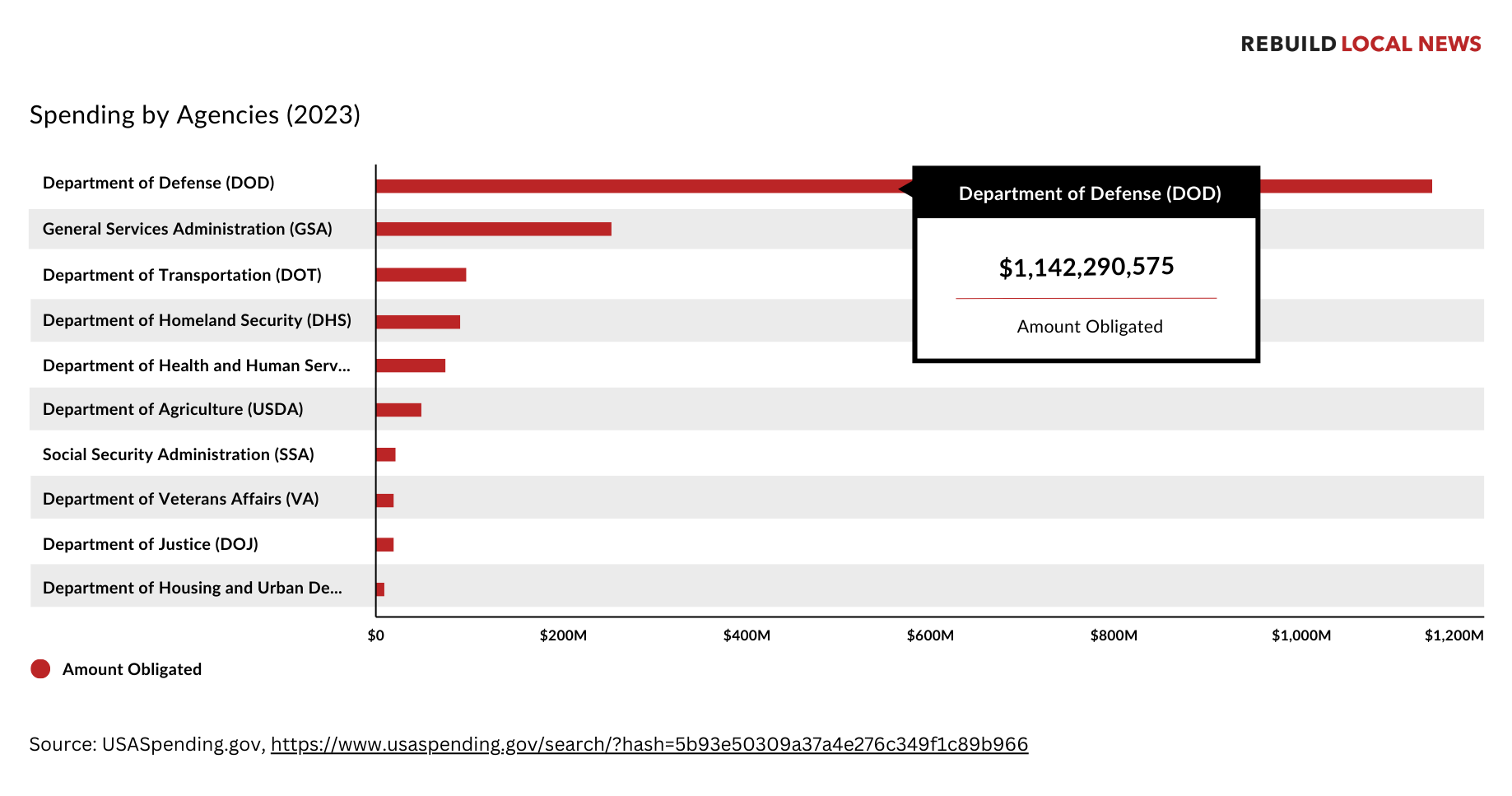

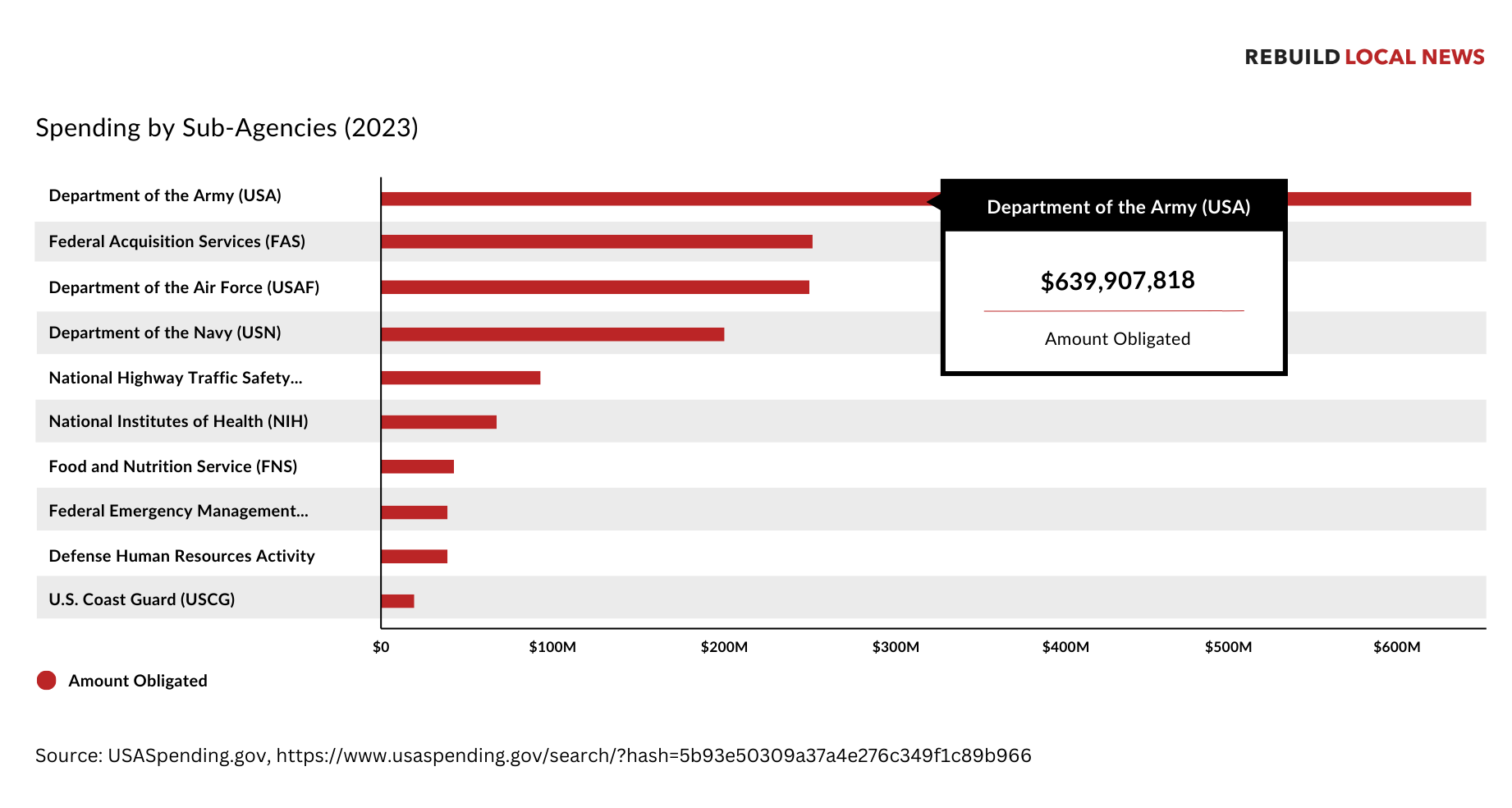

The U.S. Department of Defense is, as always, the highest spender – mostly through its recruitment campaigns. The Defense Department spent $1.14 billion on advertising in 2023. Within DoD, the Department of the Army was the top advertiser, spending nearly $640 million in 2023. One factor behind the increased advertising budget is the need to boost military recruitment. Government analysts say inflation is likely another factor, but more research is needed to explain all the forces driving the increase.

The second-highest spend, by the General Services Administration, of $253.6 million, encompasses ad campaigns across many federal agencies, including responses to natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods. Rounding out the top five spenders were Department of Transportation ($96.65 million); Homeland Security ($88.2 million); and Health and Human Services ($72.5 million). DOT advertising campaigns promoted safe driving and the rights of disabled airline passengers, among other issues. Homeland Security ads highlighted issues from emergency readiness to “See Something, Say Something” anti-crime messaging. The COVID-19 crisis drove a significant vaccination ad campaign by Health and Human Services and increased its ad spending from less than $37 million in 2019 to a peak of $453.6 million in 2022. All told, during the COVID-19 pandemic, federal agencies obligated about $1.1 billion to COVID-19-related advertising contracts, of which HHS spent $836 million, or 79 percent of the total.2 Health and Human Services advertising spending has decreased since the pandemic era peak, but not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. In 2023, HHS cut its advertising spend to just one-quarter of the prior year, to about $120 million. Similarly, overall agency spending has not declined since the end of the Covid emergency.

Limitations of Current Reporting Practices

Government agencies make public the terms of all advertising contracts awarded, including the subject of an advertising campaign, the advertising agency awarded the contract, and the contract amount. Sometimes the contract information also includes the region or population/demographic targeted. However, the contract award often does not show which specific media outlets or technology platforms received the ads. Neither the Office of Management and Budget nor the General Services Administration have an overall picture of where the ad spending is going, nor does the public.

The situation is no better on the state or local level. Researchers attempted to find out how advertising was distributed in New Jersey and Maryland, but requests were frequently rejected or went unanswered by state agencies.

This lack of transparency matters for several reasons.

First, local news in much of the country is struggling or collapsing, depriving residents of critical information, and one potential solution is ensuring that local news organizations get an adequate share of government advertising. It is difficult to design such policies sensibly without knowing how the money is currently spent.

The collapse of local news is severe. Since 2004, 2,886 newspapers have closed, and there are now 220 counties across the United States without a newspaper, according to the Medill 2023 State of Local News Report.3 Commercial advertising in newspapers has dropped 82 percent since 2000, contributing to a 57 percent drop in the number of newspaper reporters and thousands of media closures. Even though much local advertising has moved over to search engines and social media platforms, advertising is still a key source of support for news organizations – especially at the local level.4

Those few in-depth studies that have examined the distribution of advertising dollars on the local level indicate that community media does not fare well. New York City was the first city to study government ad spending. The Center for Community Media at the City University of New York’s Newmark School of Journalism found that 270 community and ethnic news outlets received only 19 percent of the city’s print and digital advertising spend in 2013 – with many receiving none at all.

A 2023 study by the Center for Community Media’s Ad Boost Initiative of New York State found that of $216 million spent across 90 advertising campaigns by six key state agencies, only 2.6% of these funds, amounting to $5.6 million, has reached community and ethnic media outlets between 2015 and 2023.

In San Francisco, only 7 of 98 community news outlets identified received any government advertising in 2023, according to a study of the city’s advertising spend by San Francisco’s Budget and Legislative Analyst. That was true even though the city had both opportunities and a need to communicate with hard-to-reach populations. For example, during the M-Pox epidemic of 2023, most prevalent among gay men, the leading LGBTQ+ publication in the city received no M-Pox vaccine advertising placements by the city.5

It appears that a substantial and growing percentage of government advertising is going to social media platforms and search engines.

-

- The Center for Community Media New York State study found that between 2012-2022, agencies spent a total of $42.4 million – or 20 percent of their total ad budget – on media placements in social media, tech and ad-serving/targeting companies. Those tech companies received almost eight times the amount that community media received.6

- Of the roughly half of San Francisco departments that did report their ad spending in FY 2022-2023, more than 40 percent of discretionary ad spending went to search and social media companies.

- The U.S. Army has shifted a large portion of its recruitment advertising to search and social media platforms.7

- A researcher at the University of Maryland found that state’s advertising spending with Google has nearly tripled since 2018.

Second, the lack of transparency can lead to cronyism. Government organizations as varied as the International Monetary Fund, the Biden administration, and The Heritage Foundation have advocated for greater transparency in government spending and procurement to prevent public money from benefitting the well-connected over the most effective and efficient vendors. Greater transparency is widely considered an essential guard against such government favoritism. Previously noted studies from New York City and San Francisco showed that before there was public scrutiny, advertising agencies failed to diversify their advertising placements among outlets – disproportionately placing ads with the largest outlets.

Third, under-served communities and their local media outlets may be left out or disadvantaged as a result of this lack of transparency. This became apparent after New York City instituted a policy requiring 50 percent of its advertising spending to be applied toward community media. More than 220 outlets received ads, some 50 of which had never benefited from city advertising. In 2019, the Haitian Times received about $200 in city advertising; in 2020, they received $73,000, including public health and census ads. The city ad revenue allowed the Haitian Times to hire freelancers, strengthen news coverage, and to increase the hours of their social media director, as well as hire a managing editor and a copy editor, its publisher, Gary Pierre-Pierre told CCM.

Because there is little clarity on who is making decisions on how major advertising campaigns are placed, local news outlets, especially small outlets, are reliant solely on advertising agencies to find and include them as vendors. Greater transparency would also support efforts from journalism groups, including the National Newspaper Association, the National Newspaper Publishers Association (which represents members of the legacy Black press), and the National Association for Hispanic Publications to pursue federal advertising dollars for their members.

This kind of spending may prove to be especially effective because hard-to-reach audiences often trust local news more than other sources of information. Local news remains the most trusted source of information by more than 70 percent of Americans across all age groups. This higher level of trust in local news is also true for Black audiences. Hispanic audiences report having the most trust in Spanish-language local news and Spanish-speaking journalists, but also trust traditional English-language local news outlets more than Spanish social media information.

A Federal Disclosure Strategy

Advocates for local news have suggested that more federal government advertising be directed toward local news. In 2011, the Federal Communications Commission report Information Needs of Communities recommended targeting federal ad spending toward local press. The impact on local news could be substantial. For instance, if the federal government followed the approach of New York City, that could direct almost $1 billion toward community news per year. In 2020, a bipartisan group of U.S. Senators issued a broader call for the Office of Management and Budget to work with agencies to direct government advertising to local news outlets to help sustain their critical information role during the COVID-19 crisis. Recent efforts by the National Newspaper Association (NNA) demonstrate a growing recognition that government agencies need to distribute advertising among a greater number of sources. An NNA-backed bipartisan policy signed into law by President Joe Biden as part of an appropriations package in March 2024 mandates that Health and Human Services set aside advertising spending on public health campaigns for placement in small and rural community media outlets. The new law focuses on only one federal agency and is limited in scope – it does not include many digital only and nonprofit news outlets; however, this kind of transparency and oversight should be implemented throughout the federal advertising budget, which could lay the groundwork for set–asides that benefit broad swaths of the industry.

Rebuild Local News supports efforts to direct advertising to local news outlets, but would also offer a more modest and obvious first step: requiring transparency. The New York City law requires that the city disclose its advertising spending. The Center for Community Media at CUNY’s Newmark School of Journalism assessed the city’s spending, and the mayor’s office is tasked with implementation and annual tracking and agency compliance. Both CUNY and the mayor’s office reports show that city agencies are becoming more compliant with the local advertising law with stronger oversight, and as a result the revenue to community and ethnic news has grown from $1 million in 2020 to around $16 million in 2023. The San Francisco city council recently agreed to report out agencies’ advertising spend and ad placement, and to focus city resources on registering small community and ethnic news sources in the city as vendors. The resolution, passed in March of 2024, also sets a goal for spending half city agencies’ advertising budgets with those local news sources.

The federal government should embrace this transparency. This approach could be administered either by the Office of Management and Budget or by the General Services Administration. As a starting point, the federal government should disclose the following on an annual basis:

-

- The overall advertising spending by each executive agency

- The names of each advertising vendor that received individual advertising contracts and the amount of the contract/s8

- The entity that received the advertising spending, including but not limited to search platforms, national news outlets, digital platforms, etc.

- The amount spent with advertising recipient, including which local news organization received which individual advertising buys, the agency and vendor responsible for that buy, and its value

Because advertising agencies already collect and provide this information to their government agency clients, making it readily available to the public is a straightforward matter of data curation and distribution. As to which federal entity would curate and distribute the data for public access, there are existing models that offer a guide. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) developed the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), the standard used by federal statistical agencies in classifying business establishments for the purpose of collecting, analyzing, and publishing statistical data related to the U.S. business economy.9 Businesses get an NAICS code classification, which could be used to identify local news outlets in government contracting documents. NAICS codes exist for newspapers (511110), for example, but do not specify what scale of newspaper – local, regional, or national. Further, the U.S. General Services Administration’s Federal Acquisition Services already produces Product and Service Codes (PCS) that identify the type of product or service being solicited or purchased by federal agencies.10 Either OMB or GSA would be potentially appropriate venues for this information. Deciding which agency would ultimately be responsible for curating and reporting this data would likely depend largely on capacity.

As for reporting and distributing the data, there are once again existing examples to rely on. The Small Business Administration prepares a scorecard annually on its procurement record with small businesses. It also regularly calculates the economic impact of its contracting set-asides in collaboration with an independent research firm; that report discloses public money allocated to existing categories of businesses, including minority-owned, service-disabled veteran-owned, women-owned and other categories that are mandated for government contracting set-asides.11 As noted earlier, the U.S. Department of the Treasury manages online databases of federal contracts through its Bureau of the Fiscal Service, which uses open data to enable tracking of federal spending on sites such as USASpending.gov and Sam.gov. The data on these websites, however, can be difficult to interpret. For example, a search of USASpending.gov reveals contracts awarded to Google, LLC, for ad placements with Adwords, but offers no details about the nature of the campaign or what other media outlets, if any, received placements as part of that campaign.

Contextualizing federal advertising spending should include an annual report of the proportion of federal agency advertising budgets being spent with local news outlets, large tech conglomerates, and other media outlets. The tools and processes for producing this kind of report already exist, with minor adjustments. Simply put, being transparent about the flow of federal ad dollars would require intention, not reinvention.

A Set-Aside Strategy

In places where the government did provide some information about the spending, oftentimes lawmakers then took the next step of requiring that a certain percentage be set aside for community news. The New York City Ad Boost initiative, which has directed more government advertising toward community news, goes farther – requiring a set-aside – and it has been successful. In Canada, up to 30 percent of provincial advertising – as much as $16 million from 2017-2019 – was being spent with Google and Facebook. Local news advocates in Ontario saw an opportunity to reprioritize provincial ad spending by allocating a portion to community newsrooms in the province. Lawmakers in Ontario recently voted to set-aside 25% of its $100 million agency advertising and public notice budget to qualified local news outlets.

Rebuild Local News has proposed legislative language for state and local governments to set aside specific amounts of their advertising for community news. A key to crafting reasonable policies is understanding that governments need to have some flexibility in how they spend. They cannot be forced to make ineffective ad buys. However, early studies show that the ad spending is not currently driven by efficiency. Sometimes governments select certain media vendors or media outlets because doing so is less time consuming and involves less work or research. Pushing government agencies to make greater efforts to reach a broader range of outlets can often produce positive results for community news without undermining the effectiveness of the marketing campaigns.

Endnotes

-

- https://www.usaspending.gov/search/?hash=5b93e50309a37a4e276c349f1c89b966

- https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-107021

- https://www.cislm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Expanding-News-Desert-10_14-Web.pdf

- https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/05/revenue-for-hundreds-of-local-news-orgs-went-up-in-2021-according-to-new-data/

- https://sfbos.org/sites/default/files/BLA_Community_Ethnic_Media_121923.pdf

- This combined total includes $1,260,326.67 in “unspecified digital media,” for which the Department of Agriculture and Markets did not identify a specific outlet. https://abi.journalism.cuny.edu/nys-ad-spending/

- https://www.military.com/daily-news/2023/01/11/new-medal-and-revised-marketing-tactics-part-of-armys-fight-against-recruiting-slump.html

- For the sake of agency efficiency, this could be a requirement over a certain contract amount.

- https://www.census.gov/naics/

- In the case of advertising, the PCS is R701

- For information on a government advertising set-aside policy, see the Rebuild Local News website at https://www.rebuildlocalnews.org/wip-government-advertising-local-news/

Acknowledgements

Rebuild Local News would like to thank those whose insights helped inform this report, in particular staff at the Government Accountability Office, Will Lennon at the University of Maryland, Darlie Gervais and Mikhael Simmonds at the Center for Community Media at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York, and Lisa McGraw at the National Newspaper Association.

Appendix

Model bill language for federal advertising spending transparency:

The annual tracking report must include a categorical breakdown of the advertising spend by:

(a) the overall advertising spending by each executive agency of the state;

(b) the names of each advertising vendor which received individual advertising contracts from an executive agency of the state and the amount of the contract(s);

(c) the entity which received the advertising spending, categorized by media type including but not limited to search platforms, national news outlets, digital platforms, local news outlets, etc.

(d) the general subject matter of the advertising placement (i.e. military recruitment, public health, job training, etc.)

References

USASpending.gov, https://www.usaspending.gov/search/?hash=5b93e50309a37a4e276c349f1c89b966

Rebuild Local News, https://www.rebuildlocalnews.org/local-news-crisis/

University of North Carolina Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, https://www.cislm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Expanding-News-Desert-10_14-Web.pdf

The News Trust Halo: How Advertising in News Benefits Brands. An IAB Research Report, https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IAB-Research-Report_Value-of-News_102720Final1.pdf

The Revenue Picture for American Journalism and How It Is Changing, Pew Research, https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2014/03/26/revenue-sources-a-heavy-dependence-on-advertising/#:~:text=Even%20under%20duress%2C%20advertising%20remains,revenue%20is%20derived%20from%20advertising.

Pew Research Fact Sheet on advertising revenue, circulation: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/newspapers/

Discourse Magazine on news revenue models,